Design Docs at Google: How to Write Effective Software Design Documents

Design Docs at Google: How to Write Effective Software Design Documents

Think writing code is your highest-leverage engineering task? Not quite. The real leverage comes before a single line of code is written—when you’re staring down a blank design doc and trying to align a dozen smart but opinionated stakeholders.

At companies like Google, design docs aren’t optional—they’re the connective tissue between engineering intent and business impact. Skip them, and you risk weeks of wasted work. Nail them, and you de-risk entire product launches.

If you’ve ever wondered how to write a software design document that actually drives clarity, decisions, and velocity, this is the playbook you’ve been looking for.

What Is a Design Doc—And Why It Matters More Than You Think

A design doc isn’t just a formality. It’s how high-performing teams make big technical bets without blowing up scope, trust, or timelines.

It’s the spec that ensures your new feature won’t get rolled back in prod. It’s the artifact that makes onboarding new engineers smooth instead of painful. It’s your pre-emptive defense against the dreaded, “Why didn’t you just use Redis?”

And at companies like Google, it’s standard. Staff Engineers spend more time in Docs than in IDEs for a reason—design documents are where engineering strategy happens.

Done right, a design doc answers one central question:

Is this the right thing to build, and are we building it the right way?

But here’s the part many engineers miss: a design doc is as much a collaboration tool as it is a technical artifact. It’s where product managers, designers, data scientists, and infrastructure teams all converge to shape the same vision. Without that convergence, “building the wrong thing” is not a matter of if, but when.

From Concept to Structure: The Flow of a Great Design Doc

When you first approach a design doc, it’s tempting to jump straight into diagrams or APIs. That’s a mistake. At Google, the best docs lead readers through a logical flow—from why this matters, to what we’re building, to how we’ll measure success.

Think of it like telling a story:

- Establish the stakes (the problem and goals).

- Present the protagonist (your proposed design).

- Show the supporting cast (owners, APIs, data stores).

- Address plot holes (alternatives, risks).

- Invite feedback before publishing the final chapter (RFC).

That’s the mindset behind the anatomy we’re about to walk through.

1. Goals: Defining the “Why” Before the “What”

Every strong design doc begins with a crisp articulation of the problem you’re solving and why it matters. This is where you set the stakes and build shared understanding.

Your goals section should answer:

- What does this project aim to achieve?

- Why now?

- How will we know we’ve succeeded?

Be specific. “Improve latency” is weak. “Reduce P95 load time on profile view from 2.1s to <1s” is strong.

Example — Weak vs Strong

- Weak: “Add caching for faster responses.”

- Strong: “Introduce Redis caching to reduce profile service P95 latency from 2.1s to under 1s, increasing user engagement by 5% and aligning with Q3 infra OKR 2.1.”

Pro tip: tie goals to team OKRs or company-wide metrics. Leadership cares less about your clever caching layer and more about how it supports growth, engagement, or infra reliability.

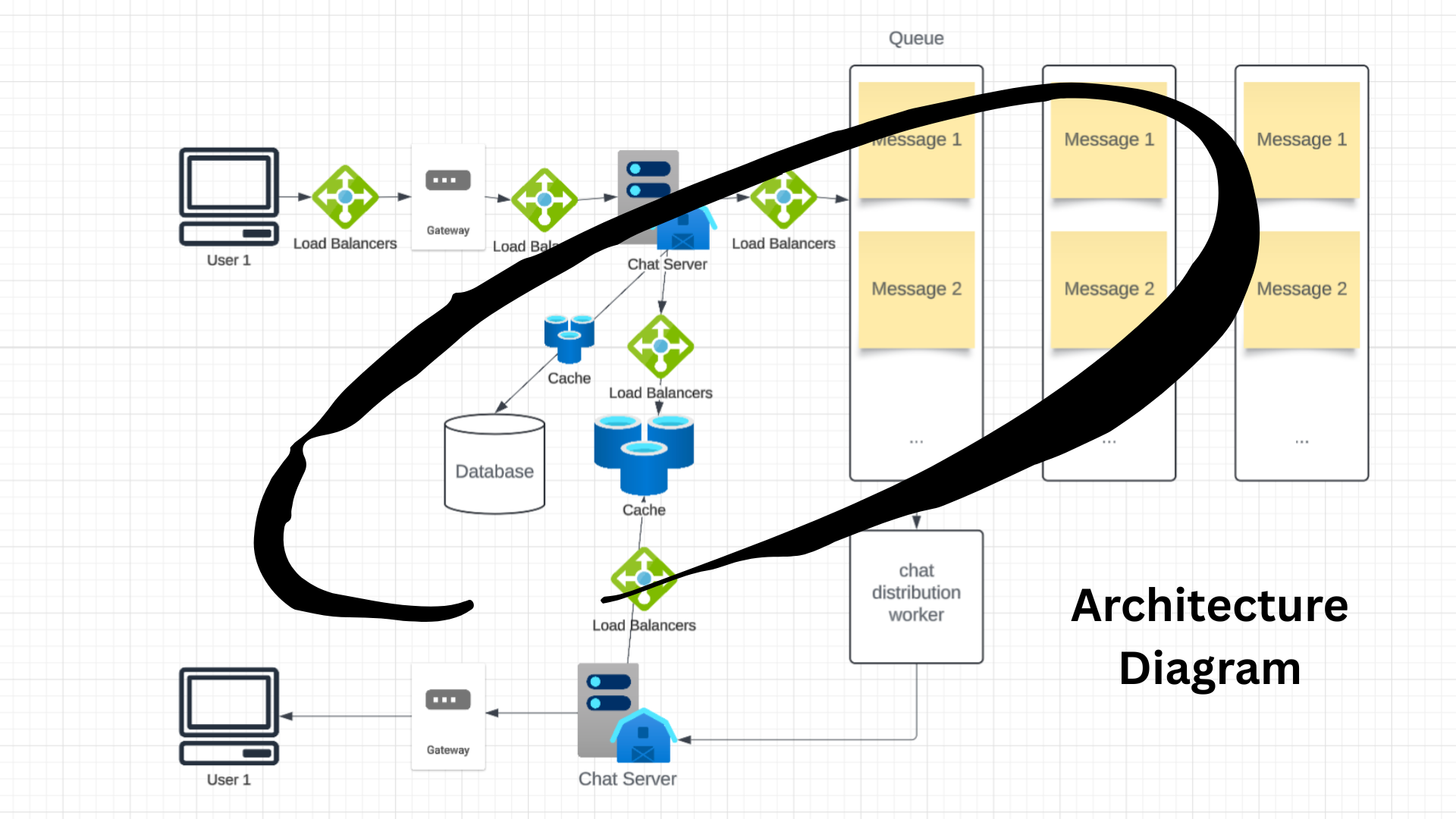

2. Architecture / System Design: The Beating Heart of the Doc

This is where most readers lean in. At Google, this section often gets the most scrutiny from senior engineers—it’s the proof you’ve thought through the system holistically.

Don’t just draw boxes and arrows. Tell the story of why this architecture makes sense and how it fits into the broader ecosystem.

Include:

- A high-level architecture diagram (if it’s not in the doc, it’s not clear enough)

- Description of each component and how they interact

- Failure modes and mitigation strategies

- Scalability, reliability, and security considerations

Example:

If you’re proposing a microservice, clarify:

- Where it sits in the service mesh

- Which existing services it depends on

- How it will handle network partitions

- Whether it’s stateless or stateful

Pro tip: Don’t get lost in premature optimization. Focus on clarity of thought, not cleverness of implementation.

3. POCs / Owners: The Human Glue

Every design needs champions. This section answers the “who” behind the “what.” Without clear owners, docs turn into abandoned wikis.

List:

- Primary engineer(s) driving implementation

- Engineering lead or EM responsible for decision-making

- Cross-functional partners (PM, designer, infra, data science)

Ownership isn’t just about accountability—it’s about alignment. Design docs often spawn follow-up work: dashboards, operational runbooks, follow-up PRDs. Make sure ownership extends beyond the initial code push.

Pro tip: Design docs with fuzzy ownership almost always result in scope creep and misaligned expectations.

4. APIs: Your Contract with the World

APIs are promises—promises that other teams and future-you will depend on. Poorly documented APIs are a tax on every future project; good APIs are leverage.

Use this section to:

- List new APIs being introduced (REST, GraphQL, gRPC, whatever applies)

- Document changes to existing interfaces

- Define request/response formats clearly

- Call out backwards compatibility considerations

Good Example:

POST /api/v2/profile

{

"user_id": "string",

"fields": ["string"]

}

Returns:

{

"profile": { "name": "string", "age": "number" },

"last_updated": "ISO8601-timestamp"

}

Pro tip: When in doubt, over-specify. Future-you will thank present-you.

5. Data Storage: More Than Just Tables

How and where you persist data determines not just performance, but compliance, scalability, and cost.

Include:

- Database or storage solutions (SQL vs NoSQL, cold vs hot storage)

- Schemas and indexing strategy

- Retention and archival plan

- GDPR/compliance considerations if applicable

Don’t forget migration plans. If you’re touching production tables, you need a safe rollout strategy. At Google, a “two-phase deploy” (write to both old and new tables, then cut over reads) is common to avoid downtime.

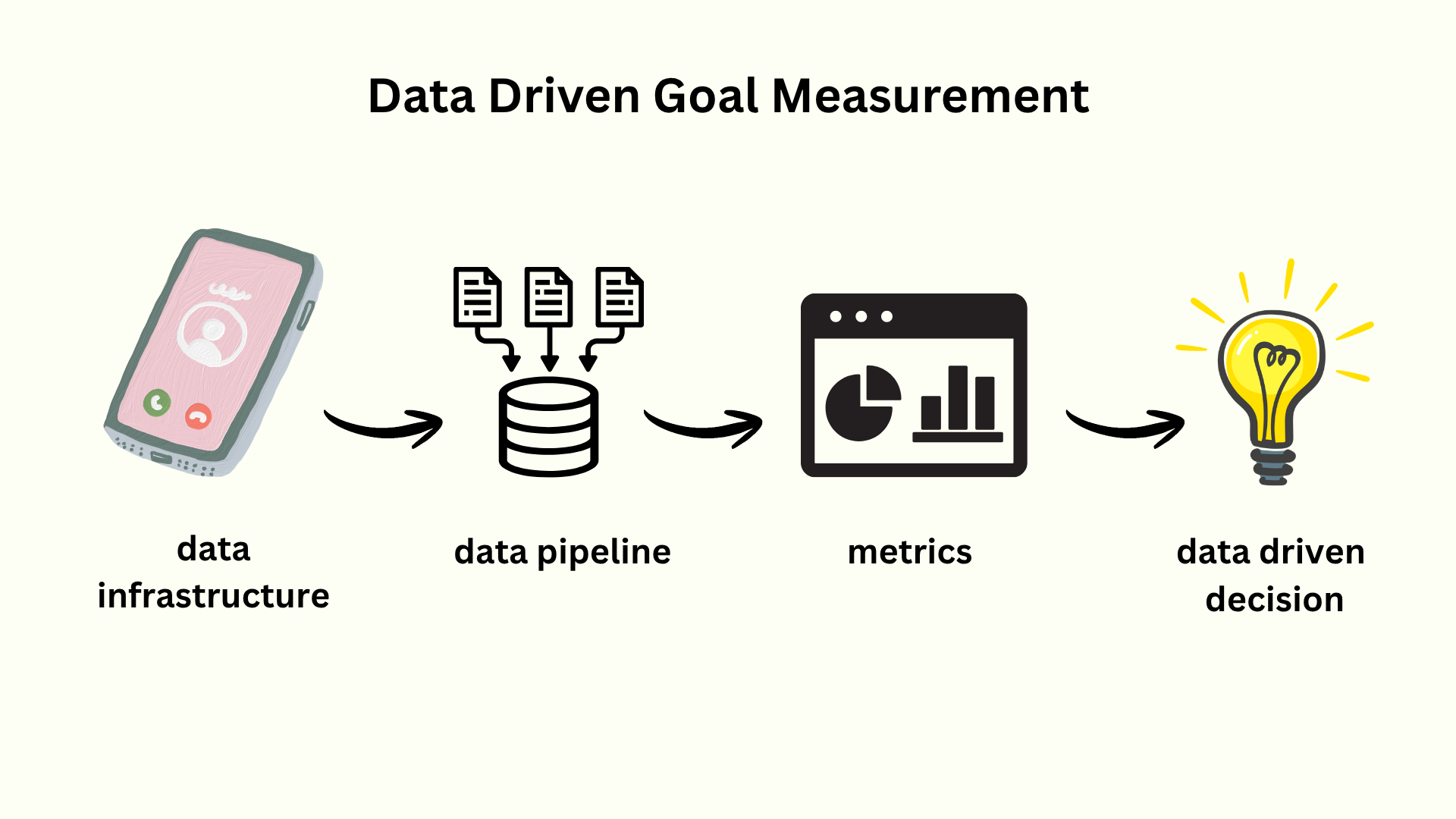

6. Results / Metrics: The Part Most People Skip

This is the section that separates mediocre docs from great ones. Without clear success metrics, even “finished” projects can be seen as failures.

Spell out:

- How success will be measured

- What metrics you’ll track (latency, error rate, conversion, engagement)

- How you’ll gather the data (dashboards, logging, experiment frameworks)

- Whether you’re running an A/B test, canary, or phased rollout

Pro tip: Treat this as your metrics review plan, not an afterthought. It’s how your work gets defended in postmortems, praised in promotions, and funded for v2.

7. Alternatives Considered: Show Your Homework

This isn’t a “cover your ass” section—it’s proof of rigorous thinking.

Discuss:

- The paths you didn’t choose—and why

- Tradeoffs involved in your chosen design

- Any risks you’re accepting knowingly

Always include “do nothing” as a baseline. Sometimes the best move is to not build anything. This section also helps future engineers understand your decision-making context.

8. Request for Comments (RFC): Invite the Right Critique

Your doc isn’t done when you stop writing—it’s done when you’ve invited critique and incorporated it.

An RFC section should:

- Tag key reviewers (senior engineers, TLs, infra teams, etc.)

- List unresolved questions

- Set a clear deadline for comments and final decision

Good RFCs avoid back-channel debates, “I thought we agreed…” moments, and last-minute surprise objections.

Design Docs Aren’t Bureaucracy—They’re Leverage

The best engineers don’t just ship code—they shape decisions. And design docs are how you do that.

They force clarity before complexity. They surface edge cases early. They create alignment across roles. And yes, they save you from rewriting half your system six weeks in.

So next time you’re tempted to skip the doc and “just start coding,” pause.

Remember: the best engineers at Google didn’t get there by being the fastest to open their editor. They got there by making the smartest technical decisions—and documenting them so well that anyone else could understand, review, and build on top of them.

You don’t need to be Staff+ to write great design docs. But writing great design docs is one of the fastest ways to get there.

✉️ Get free system design pdf resource and interview tips weekly

✉️ Get free system design pdf resource and interview tips weekly